historical injustice in the urban environment: the ecological implications of residential segregation in indianapolis

Environmental inequities result from a number of factors—lack of access to parks and recreation; exclusion from public participation in the environmental decision-making process; or lack of knowledge, resources, or political clout to oppose environmentally-hazardous sitings. Yet many of the underlying causes of environmental injustice extend from the long-term governmental failure to remedy a deeply-entrenched system of racial discrimination. As a result, the environmental benefit/burden disproportionality reflects, in many ways, a de facto form of discrimination rooted in a history of social, political, and economic exploitation—from housing segregation, redlining, school segregation, and limited employment opportunities. Accordingly, the environmental justice movement cannot be understood without this historical frame of reference.

The following case study provides a historical overview of housing segregation in Indianapolis and its long-term impact on the environmental quality of the city's neighborhoods and communities. The interactive timeline, located at the bottom of this page, introduces readers to other important historical developments throughout the State of Indiana in the quest for environmental justice.

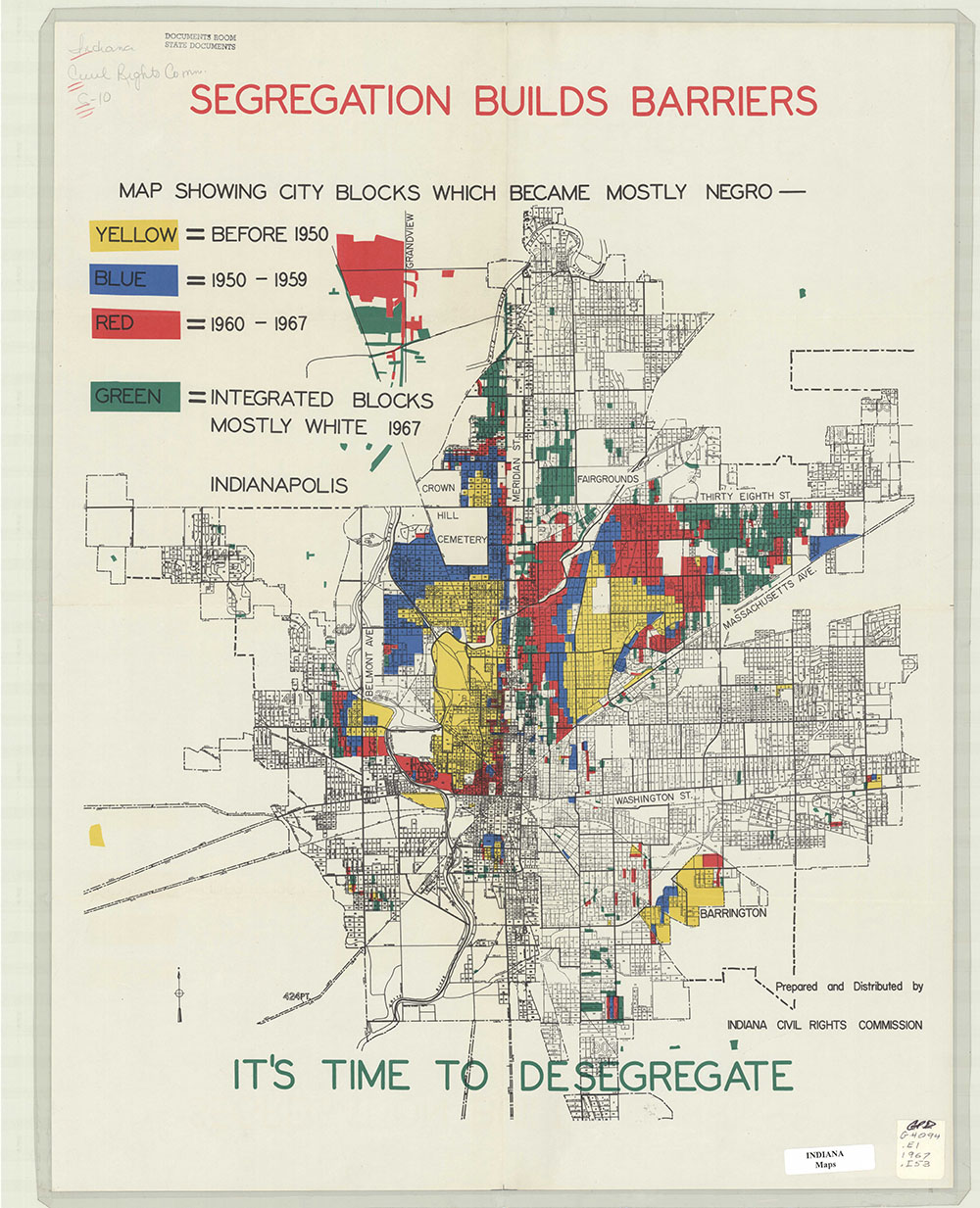

RACIAL ZONING, "Redlining," AND the african-american housing shortage: THE SOCIOECONOMIC CONTEXT

Since the early 1900s, zoning has been the principal method of land-use planning and regulation at the municipal level of government. The city’s ability to zone extends from its “police power,” the authority of states and their political subdivisions to enact measures in preserving the “health, safety, morals, and general welfare” of the people. In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court sanctioned the municipal exercise of a police power over land use in the definitive case of Village of Euclid v. Amber Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365.

The idea that zoning simply relates to local concerns over shaping the built environment ignores the social and economic implications of land-use planning and regulation. Zoning, along with other land use controls, can affect environmental quality, public service provisions, income and wealth distribution, patterns of commuting, natural resource development, and even national economic growth.

In 1917, the U.S. Supreme Court declared racial zoning unconstitutional in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60. However, for several years following this decision, a number of cities either revised their racial zoning ordinances or enacted new legislation in an attempt to distinguish their laws from the ordinance declared void in Buchanan and thus circumvent the Court's holding.

In 1926, the Indianapolis City Council, heavily influenced at the time by the Klan, drafted a residential zoning ordinance prohibiting blacks from moving into predominantly white neighborhoods without the consent of the white residents, and vice versa. Despite doubts among legal staff from the mayor’s office as to its constitutional validity, the measure enjoyed broad support from white civic organizations and municipal officials alike. Proponents of the bill cited the recent decision of Tyler v. Harmon, 158 La. 439 (1925). In that case, the Supreme Court of Louisiana upheld the constitutionality of a New Orleans racial zoning ordinance—a model upon which the Indianapolis measure was based—concluding that, because the ordinance prohibited mere occupancy rather than the sale of property, Buchanan did not apply. The court further reasoned that, because it applied equally to whites and blacks and dealt with “social, as distinguished from political, equality,” the ordinance lacked a discriminatory basis. The Tyler decision was sufficient precedent for Indianapolis officials to act. “Passage of this ordinance,” declared the president of the White Citizens Protective League, “will stabilize real estate values . . . and give the honest citizens and voters renewed faith in city officials.”

Litigation ensued when Dr. Guy Grant, an African-American physician, breached a contract with Edward Gaillard for the purchase of a home in a predominantly white Indianapolis neighborhood. Grant based his refusal on the grounds that the ordinance would have prevented him from occupying the property. Attorneys from the local chapter of the NAACP joined the suit and filed a petition seeking to overturn the ordinance on constitutional grounds. The trial court agreed and, relying on Buchanan, declared the zoning ordinance void. Attempts to appeal the case dissolved when the U.S. Supreme Court held the New Orleans’ ordinance unconstitutional in Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U.S. 668 (1927).

Absent the municipal authority to enact racial zoning ordinances, advocates of segregated housing relied principally on two alternatives: (1) racially-restrictive covenants; and (2) “redlining,” the government-sanctioned practice of denying mortgage loans based on race and ethnicity.

On June 13, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law one of the most economically-significant pieces of federal legislation in U.S. history. The Home Owners Loan Act of 1933 introduced Americans to the long-term, low-interest, self-amortizing mortgage. To help stabilize the ailing real estate market, the Act created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), the federal agency responsible for refinancing home mortgages at risk of default or foreclosure. Approximately 40% of eligible persons in the U.S. sought assistance under the program. Yet despite its success, the national policy of homeownership and foreclosure prevention failed to apply equally, closing the door on the American dream for blacks and other minorities.

Because of the inherent risk involved with mortgage financing, the HOLC introduced standardized appraisal methods to determine the “useful or productive life of housing” prior to issuing a loan. According to author Kenneth Jackson, “HOLC appraisers divided cities into neighborhoods and developed elaborate questionnaires relating to the occupation, income, and ethnicity of the inhabitants and the age, type of construction, price range, sales demand, and general state of repair of the housing stock.”

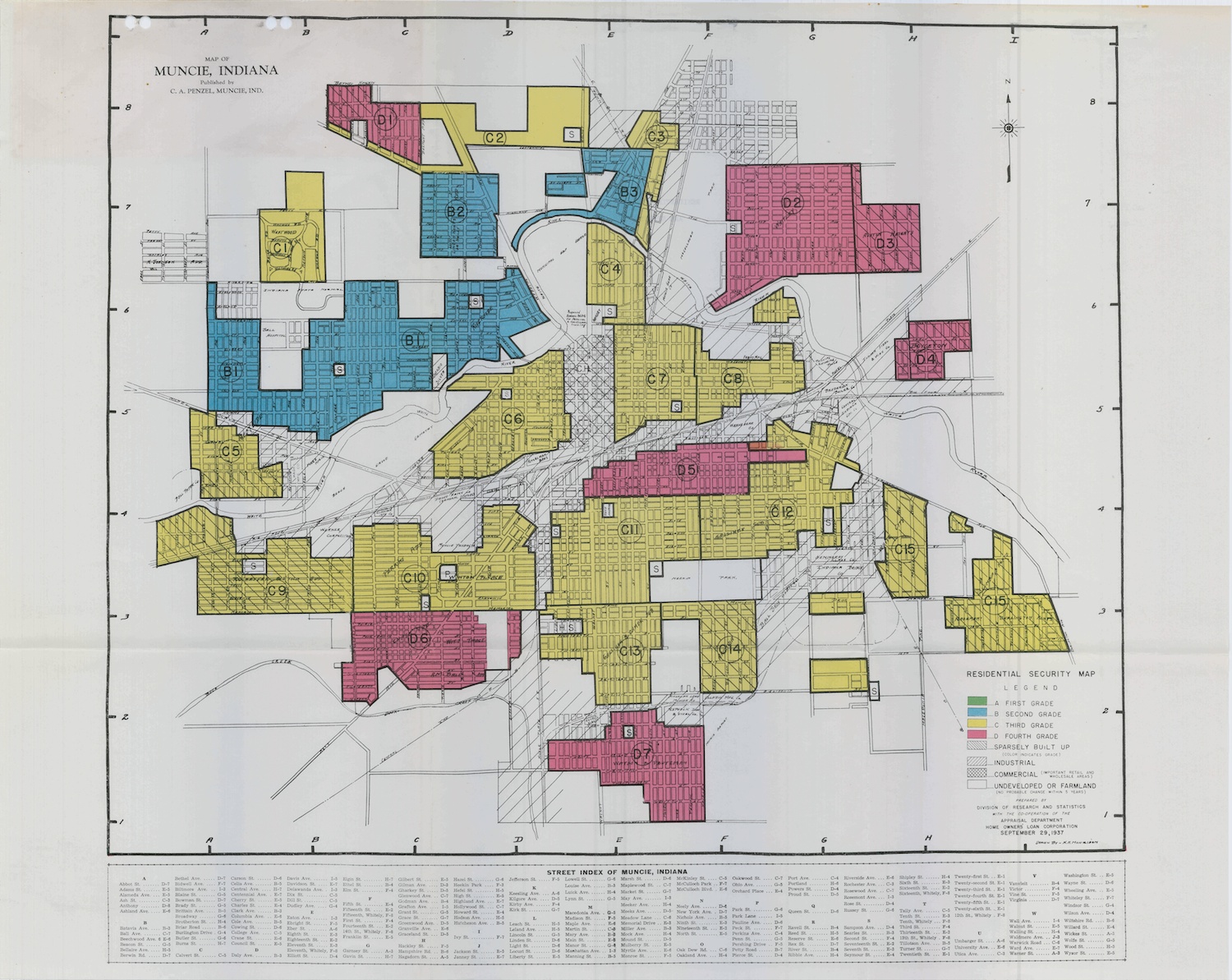

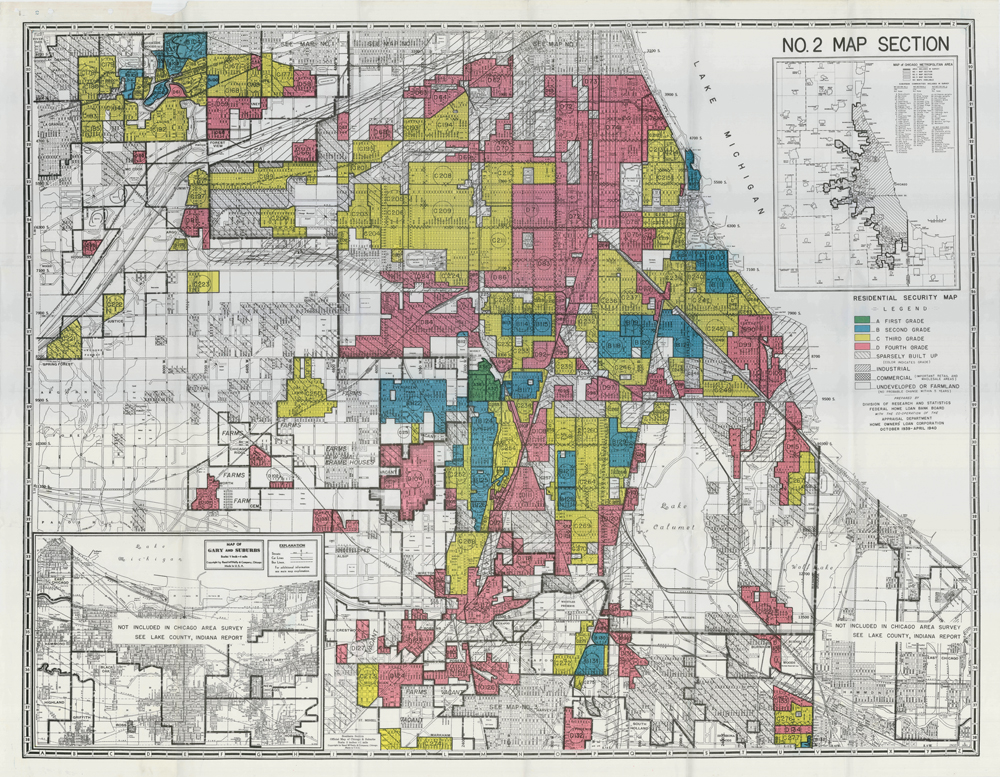

Using this data, the HOLC devised a four-tier rating system for classifying a particular neighborhood’s projected economic stability. HOLC “Residential Security Maps” categorized each neighborhood by letter and color—ranging from first-grade neighborhoods, described as new, homogeneous, and “in demand” (A, green), to undesirable areas depicted as having fully declined in property value (D, red).

The Federal Housing Authority (FHA)—established under the National Housing Act of 1934 to regulate mortgage terms and interest rates for the loans that it insured—modeled its Underwriting Manual on the HOLC appraisal system. The Manual candidly stated that, “if a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.” To help ensure housing stability, the guide further recommended “subdivision regulations and suitable restrictive covenants.”

Residential demographics in Indianapolis during this period reveal the extent to which redlining helped preserve the status quo of housing segregation. As historian Richard Pierce observes, in his study on the politics of race in Indianapolis from 1920 to 1970, an overwhelming majority of black families in the city resided in D areas. For example, "[i]n one blighted neighborhood, catalogued as D-25, African-Americans made up 90 percent of the population.” There were no black families that lived in the A areas, and only two resided in one of the city’s seventeen B neighborhoods. Another Indianapolis neighborhood, according to a HOLC appraisal, consisted of a “better class of Negroes, including teachers, doctors, etc., many of whom are home-owners. Local lending institutions are satisfied to make loans to people in this class in this neighborhood.” However, the neighborhood was still classified as D-27, evidence that class distinctions made little difference under the appraisal system.

“In one blighted neighborhood, catalogued as D-25, African-Americans made up 90 percent of the population.”

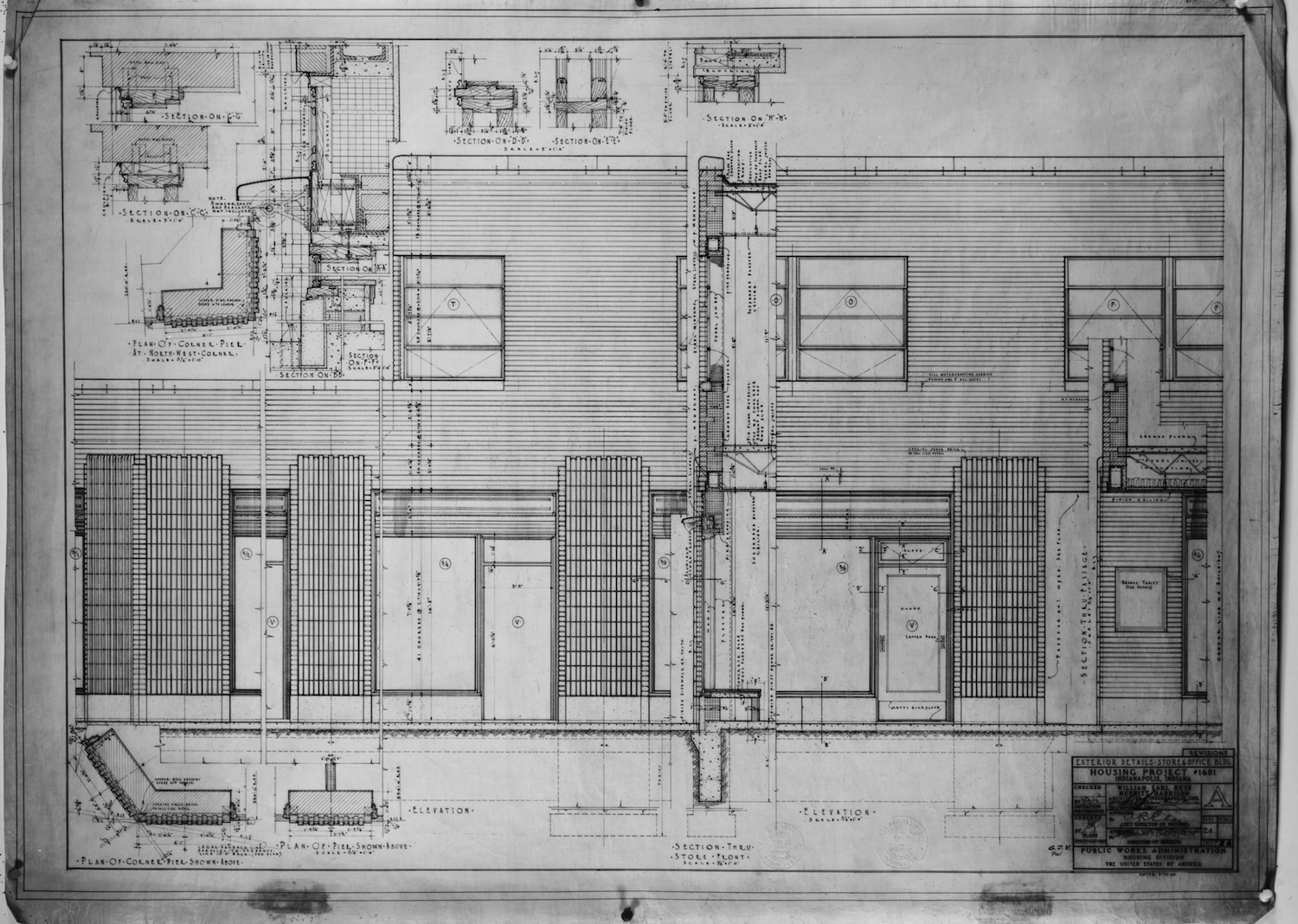

By the 1930s, the proliferation of racially-restrictive covenants and rental discrimination in Indianapolis had led to a severe housing shortage for African-Americans, which in turn induced overcrowding, structural disrepair, inadequate sanitation, and price gouging. An effort to alleviate these conditions began in 1934 with the construction of Lockefield Gardens, a public housing complex located on Indiana Avenue, near one the city’s oldest black neighborhoods. Initiated by the Housing Division of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works and the Advisory Committee on Housing of Indianapolis, the project appealed to city officials because, although aimed at mitigating the housing shortage, it helped preserve residential segregation. At the same time, however, the development provided several hundred African-American families with a healthy living environment. According to Richard Pierce,

Lockefield Gardens was a community rather than simply a collection of residential structures; the plan included an elementary school, a play yard, and ample living space between and behind apartment buildings. Developers believed that children needed space to play and that families needed an area to call their own—a relatively novel idea in the late 1930s. Row houses were placed facing a central mall, or green, which was a large, landscaped area. Designers used only one-fourth of the physical space allocated to the project for the actual buildings, the rest was landscaped.

Whatever its merits or drawbacks, the Lockefield Gardens project failed to alleviate the increasingly severe housing shortage. In the years following the Second World War, housing discrimination continued to plague black families living in Indianapolis. When city officials declined federal aid for additional public housing, African-Americans took a novel approach to meet their residential needs. In 1946, the Flanner House, a social service center for the Indianapolis African-American community, petitioned the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission to purchase land north of Crispus Attucks High School for redevelopment. In exchange for land and building materials, African-American clients were to invest “sweat equity” by providing the labor. As the largest self-help housing program in the U.S. at the time, Flanner House constructed over 330 homes between 1950 and 1964.

City leaders and many throughout the African-American community hailed the project as a success. And with good reason. Among those families that participated, only four lost their homes to foreclosure. However, the program was not without its critics, including leadership among the NAACP. Not only did the project help maintain segregated housing patterns by concentrating redevelopment efforts in a predominantly African-American neighborhood, but it displaced existing poor residents to the benefit of a smaller middle-class.

the precarious path to progress: HOUSING DESEGREGATION, PARK PRESERVATION & THE CASUALTIES OF "URBAN RENEWAL"

As with Lockefield Gardens, the Flanner project—with an average annual construction of just over 30 homes—did little to relieve the housing shortage in Indianapolis. By the early 1960s, legislative reform seemed to be the only way to ensure fair housing for African-Americans. In 1964, Indianapolis Mayor John Barton, prompted by a growing civil rights movement and the strong urging of Governor Matthew Welsh, commissioned the drafting of open housing legislation. Sponsored by Rev. James L. Cummings and Rufus Kuykendall (the only two African-American members of the city council at the time), General Ordinance 56-1964 prohibited discriminatory practices in the sale, lease, rental, or financing of property “because of race, color, religion, ancestry or national origin.” The ordinance passed, but not before it was amended to omit clauses prohibiting racially restrictive covenants and real estate brokers from influencing prospective homebuyers by referring to a particular neighborhood’s racial composition. In short, the ordinance’s lack of genuine force presented little more than a token effort toward fair housing in Indianapolis.

Despite the persistence of segregated housing during the 1950s and 1960s, a few neighborhood associations—including the Highland-Kessler Civic League, the Devington Communities Association, and the Spring Mill Hoover Association for Residential Participation—challenged the status quo, some with greater success than others. In 1956, a group of black and white families formed the Butler-Tarkington Neighborhood Association, which sought to promote “better communication among the residents” while “preventing inter-group conflicts.” The BTNA’s ultimate goal was to maintain the “quality of the neighborhood” while establishing a strong “sense of community among the residents.” While portions of the neighborhood remained disproportionately white or black, the BTNA demonstrated that, contrary to popular belief, residential integration did not necessarily precede depreciation in property values.

The BTNA’s preservation of Tarkington Park illustrates an uncommon form of environmental justice in Indianapolis at the time. By the late 1950s, the park—bounded to the north and south by 40th and 39th Streets and to the east and west by Meridian and Illinois Streets—had fallen into serious disrepair from years of neglect. Local businesses targeted the park for commercial development, seeking to transform the green space into a parking lot. However, the BTNA persuaded the Metropolitan Planning and City Parks Departments to preserve the park through funding and maintenance staff, providing the neighborhood with a safe and sanitary recreational environment.

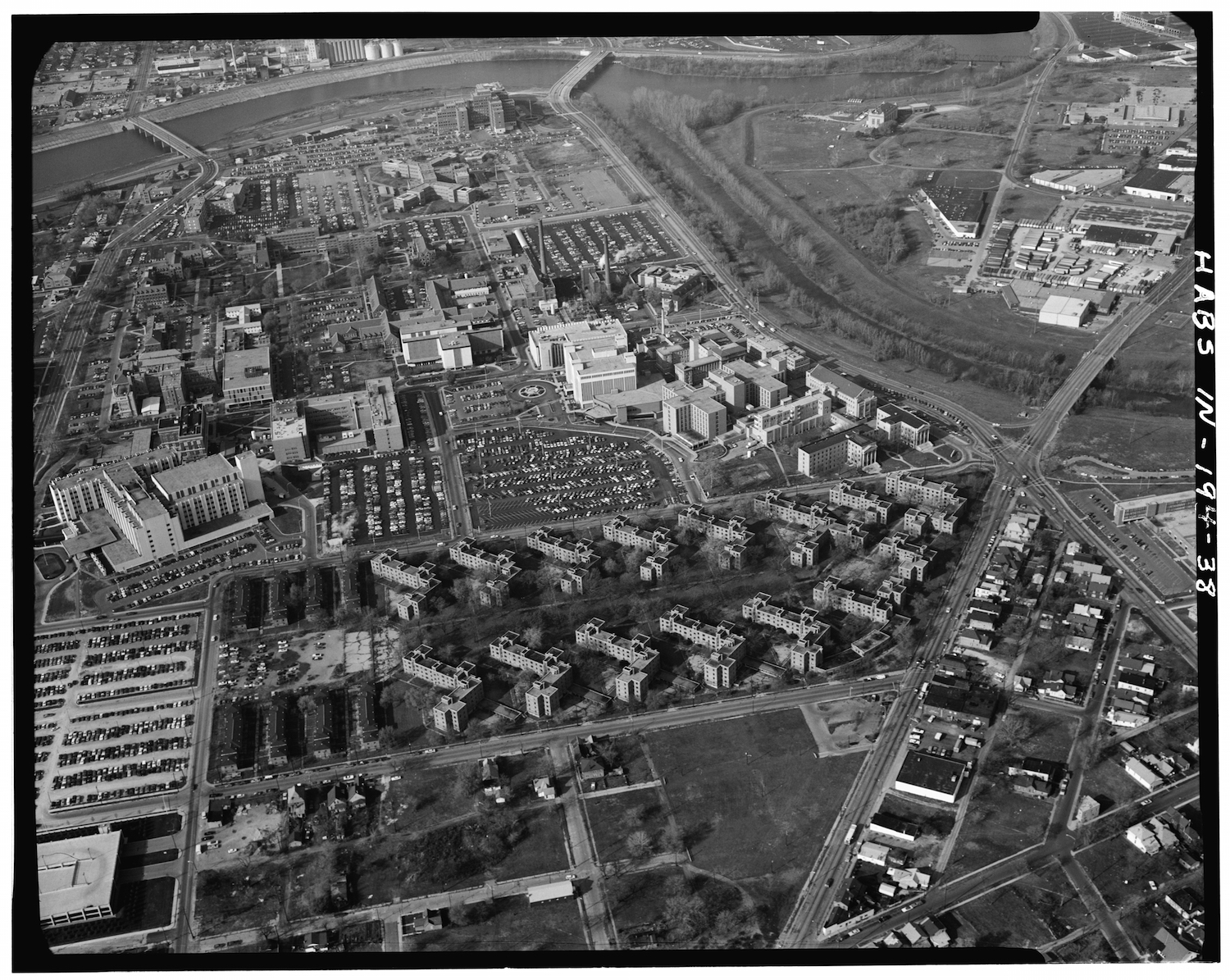

Unfortunately, successful efforts at residential integration and environmental preservation failed to extend much beyond the neighborhood boundaries of Butler-Tarkington. Instead, many of the traditionally African-American neighborhoods of Indy’s urban core succumbed to the “urban renewal” programs of the 1950s and 1960s. City officials sought to clear “blighted” areas rather than revitalize them, transforming the physical environment at great social and cultural expense.

As government subsidies shifted away from urban redevelopment, suburban sprawl added to the costly extension of public services to outlying, metropolitan areas. Perhaps the most well-known urban residential casualty was the neighborhood surrounding Indiana Avenue. By the early 1970s, the once-vibrant African-American community had given way to the construction of I-65 and the IUPUI campus. Today, only a few historic buildings—including the Madame Walker Theatre—remain as testaments to the neighborhood’s legacy.

The diversion of public funding and private investment in downtown Indianapolis led to further decline in the urban environment. Housing abandonment, demolition by neglect, mortgage foreclosure, and declining property values plagued several neighborhoods during the last decades of the 20th century. To make matter worse, many of the businesses that had served local needs—including supermarkets and small, black-owned establishments—closed their doors, leaving residents with limited access to healthy food or basic goods and services at affordable prices.

The Fall Creek neighborhood—bounded by Meridian Street to the west, Fall Creek Parkway to the north, College Avenue to the east, and 22nd Street to the south—illustrates the rapid decline of the physical environment during these years. By the early 1980s, following years of disinvestment, the neighborhood—formerly referred to as “Dodge City” because of its high crime rate—consisted largely of vacant lots and abandoned homes. Although many low-income, minority families continued to reside there, the city directed few resources to help repair the area’s increasing blight.

toward environmental equality: A CIVIL RIGHTS ACTION ON COMBINED SEWER OVERFLOWS

The disinvestment of Indy's downtown neighborhoods following the “urban renewal” programs of the 1950s and 1960s not only created a landscape of blight and disrepair, but also left an aging, broken, and unsanitary infrastructure. Perhaps most representative of this environmental injustice was the city's outdated combined sewer system, which was literally flooding (in fact, continues to flood) many urban residential areas with raw sewage.

A relic of early-20th century urban development, combined sewer systems were designed to collect rainwater runoff, domestic sewage, and industrial wastewater in the same pipe for conveyance to a sewage treatment plant. However, during periods of heavy rainfall or excess snowmelt, these systems were specifically engineered to overflow and discharge excess wastewater directly into nearby streams, rivers, or other bodies of water. These “combined sewer overflows” (CSOs) contain untreated human and industrial waste, toxic materials, and other hazardous pollutants. Although federal law prohibited construction of combined sewer systems after July 1, 1977, the EPA and most state environmental programs failed to address the CSO problem until the late 1990s.

In 1987, the EPA delegated responsibility for CSO permitting to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management. However, absent strict federal regulations, there was little incentive to comply with water quality standards under the Clean Water Act. And because most urban communities in Indianapolis (as with many others across the U.S.) lacked the resources or political strength to enforce these standards, they were left to suffer from the environmentally hazardous legacy of these outdated sewer systems. In adding insult to injury, the growth in suburban residential developments led to even heavier sewage overflow in Indy's downstream urban neighborhoods.

In 1999, two environmental justice organizations—Improving Kids’ Environment and the Hoosier Environmental Council—filed an administrative complaint with the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights on behalf of minority residents of the Fall Creek and White River neighborhoods (the population of which, at the time, was more than 85% black). The complaint alleged, among other things, that the city—while investing limited resources in new suburban residential developments—had failed to remedy CSOs in the urban neighborhoods, resulting in a disproportionate environmental impact in violation of EPA’s Title VI regulations. In 2001, the EPA accepted the complaint for investigation, ultimately leading to a settlement in which Indianapolis agreed to a long-term CSO control plan aimed at eliminating the discriminatory effects of the city's obsolete sanitation services. The consent decree into which the parties entered in 2006 requires the capture and treatment of 95% and 97% of the sewage overflows in the White River and Fall Creek watersheds respectively.

Contemporary developments in the Fall Creek neighborhood yielded further gains for environmental justice advocates. In 2001, the City of Indianapolis partnered with several private investors to revitalize the neighborhood. The King Park Development Corporation (KPDC)—a “non-profit community development corporation committed to improving housing, economic development, and quality of life”—managed the project, with assistance from the Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana. Project planning involved a steering committee of city leaders, local residents and business owners, and other stakeholders to ensure meaningful community involvement in the revitalization process and sustained or improved property ownership stability and affordability. Today, according to the KPDC, there are over 400 homes in Fall Creek Place, and “the neighborhood is much ‘greener’ than before, with one new city park, three new neighborhood parks and a new linear greenway along Fall Creek."

Urban Revitalization: Community Empowerment or Adverse Impact?

Revitalization projects such as the development of Fall Creek Place have great potential for boosting the local economy and stimulating environmental recovery, leading to increased public health and enhanced quality of life for many urban residents. The costs and benefits of this process, however, are not always proportional to the stakeholders involved. Adverse impacts, while often unintended, may result from a lack of community involvement or input from existing residents. “Gentrification”— the displacement of existing, typically lower-income residents as a result of increased property values and taxes—represents a particularly harmful impact.

The socio-economics of urban revitalization are complex and present unique challenges to each community. However, adverse impacts can often be mitigated through careful planning and effective communication. While it is important to identify the interests of public and private investors, it is equally important to include members of the community as key decision makers in the process. The goal is to identify a variety of creative solutions to accommodate the mix of community needs and interests.

conclusion: finding common ground

Indianapolis has come a long way since the housing segregation policies and “urban renewal” programs of the early to mid-20th century. In recent years, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management has shown a promising commitment to furthering the goals of the environmental justice movement. Moreover, the city’s long-term CSO control plan promises to improve the quality of life for many urban residents through environmental restoration and, consequently, economic revitalization.

These small, albeit important, indicators of progress should not, however, distract from other areas in need of change. Today, for example, Tarkington Park seldom receives visitors, having once again fallen into disrepair from neglect and rising crime in the area. In 2012, a collective of neighborhood residents, local businesses, city officials, and other key stakeholders proposed a $5 million redevelopment plan for the park, aiming to stimulate investment in the surrounding retail and residential areas. The revitalized park would also provide a healthy recreational environment for local residents. However, financial commitment to these plans has yet to be fully realized.

The story of environmental justice contains multiple narratives. Community leaders, public officers, local residents, lawyers, politicians, waste facility operators, environmental officials, and others possess a variety of unique interests—some competing, some shared. As the environmental justice movement expands and draws greater public involvement, its success depends in large part upon building bridges and forging a stronger community ties.

Sometimes, shared interests result from a process of deliberative negotiation. Opportunities for public participation in the environmental decision-making process have become more democratic and consensus-driven in recent years. In several states, for example, local advisory committees are appointed to assess and report on the social, economic, and environmental impact of proposed waste facility sitings. Other times, external forces provide the necessary catalyst for collaboration and change. The CSO litigation, for example, brought together a range of organizations in support of environmental justice, including Concerned Clergy, the Sierra Club (one of the traditional “Big Green” organizations) and local neighborhood associations. Other strategies in achieving environmental justice include legislative and political advocacy, media campaigns, community outreach and public education, translation services for non-English speaking communities, and other creative approaches.

The ultimate goal, of course, is not simply to reallocate environmental burdens so that all communities suffer equally. To the contrary, environmental justice seeks pollution protection for all persons, regardless of income, race, or ethnicity. However, until that goal is realized, those without the technical know-how, resources, or political clout to protect their own interests deserve greater advocacy from the community at large.

SOURCES

Bullard, Robert D., ed., The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution (2005).

Cole, Luke W., and Sheila R. Foster, From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement (2000).

Hurley, Andrew, Class, Race, and Industrial Pollution in Gary, Indiana, 1945-1980 (1995).

Jackson, Kenneth T., Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (1985).

Pierce, Richard B., Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970 (2005).

Rector, Josiah, Environmental Justice at Work: The UAW, the War on Cancer, and the Right to Equal Protection from Toxic Hazards in Postwar America, 101 J. Am. Hist. 480 (2014).

Roisman, Florence Wagman, Property and Human Rights (2012).

Silver, Christopher, The Racial Origins of Zoning in American Cities, in Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows (June Manning Thomas & Marsha Ritzdorf, eds. 1997).

Thornbrough, Emma Lou, African-Americans, in Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (David J. Bodenhamer & Robert G. Barrows, eds. 1994).

Thornbrough, Emma Lou, Segregation in Indiana During the Klan Era of the 1920’s, 47 Miss. Valley Hist. Rev. 594 (1961).

Waterhouse, Carlton, Abandon All Hope Ye That Enter? Equal Protection, Title VI, and the Divine Comedy of Environmental Justice, 20 Fordham Envtl. L. Rev. 51 (2009).