INTRODUCTION

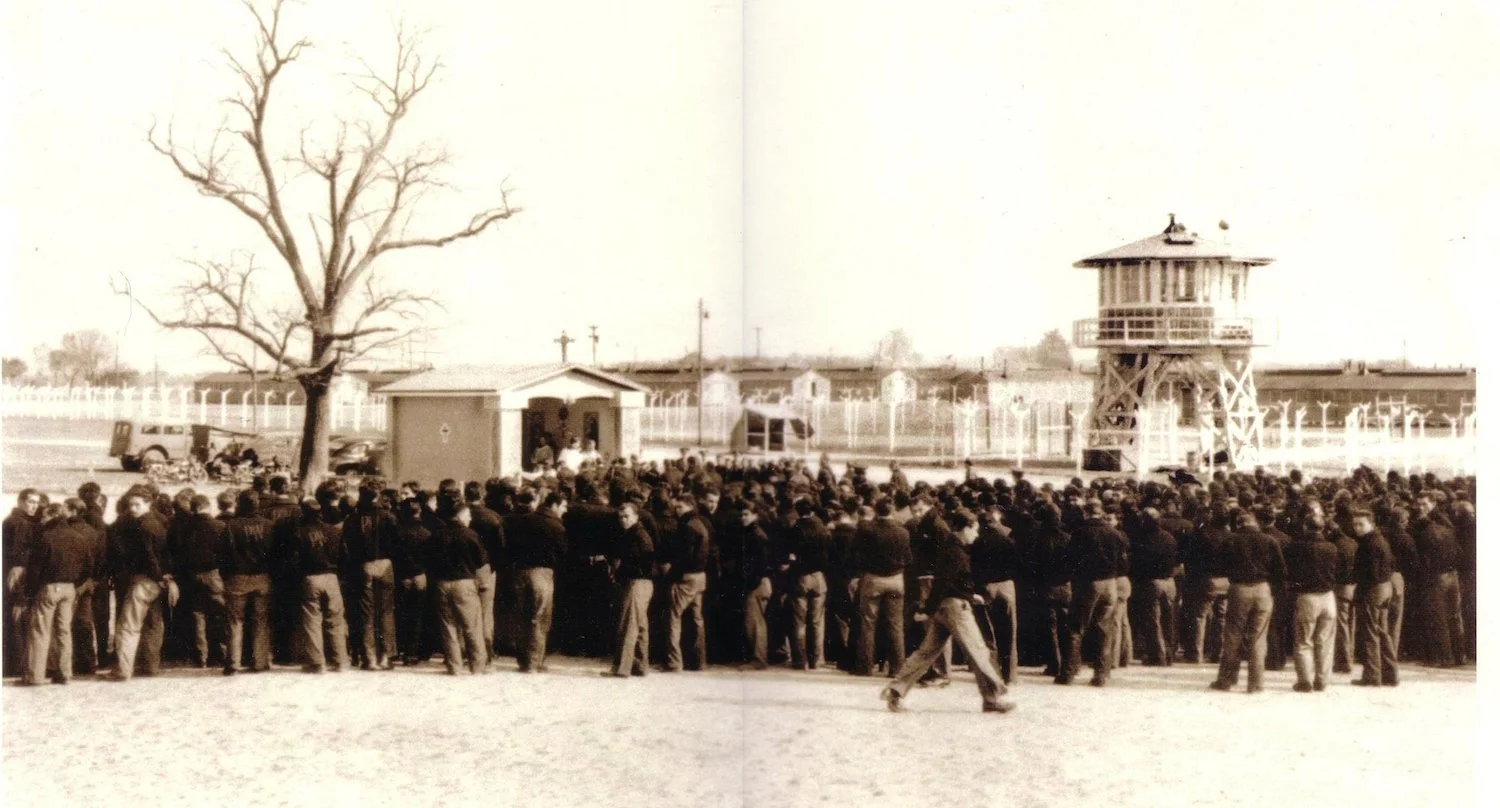

On the morning of August 24, 1944, the residents of Windfall, Indiana, a small rural community located just southeast of Kokomo, gathered at the Mill Street railroad crossing, anxiously awaiting the arrival of recently-captured German prisoners of war. County officials had refused to provide details, but rumors had been circulating for over a month that an estimated one to two thousand enemy POWs would be sent to this town of just over 800 residents. The Tipton Daily Tribune had reported earlier in the week on the arrival of camp guards and military officers and that the prisoners were expected “within the next few days.” With the arrival of the train that August morning, local residents watched with mixed emotions as the first group of prisoners, under heavy guard, disembarked and proceeded to march to their camp located at the east edge of town, adjacent to the local high school.

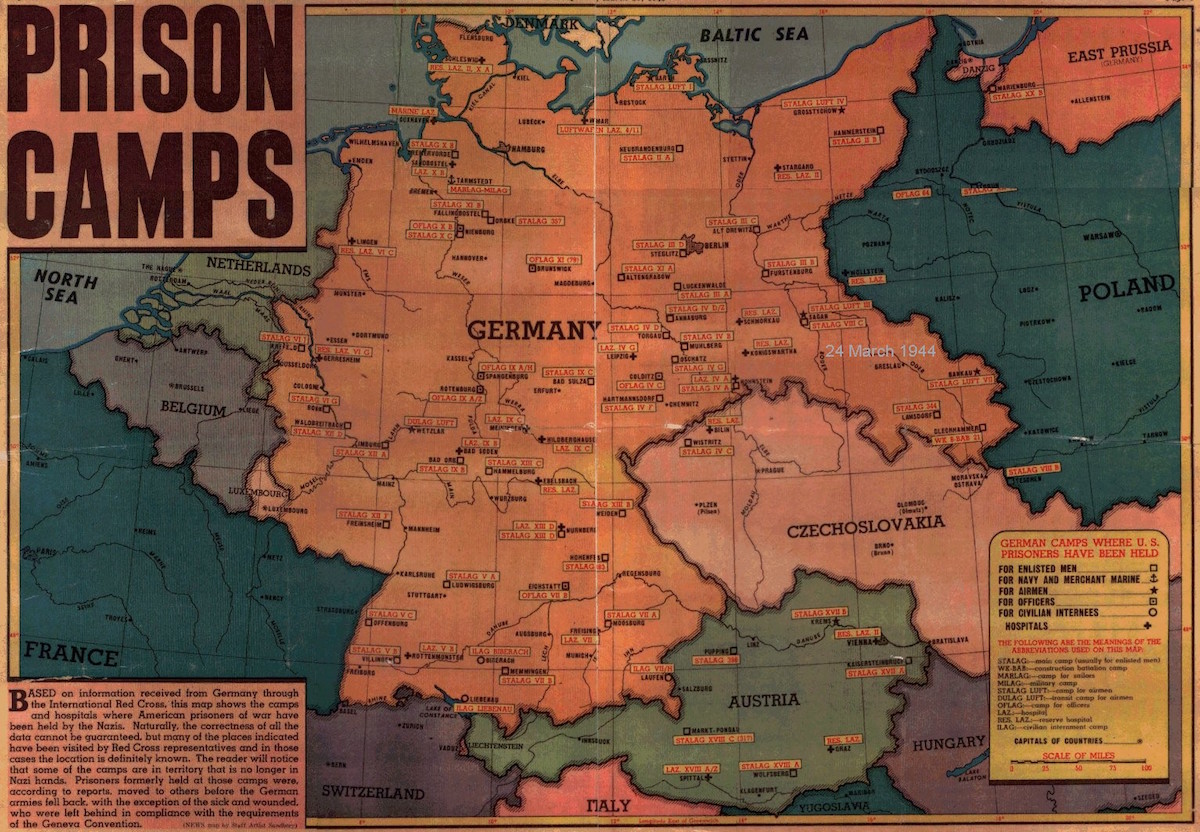

Thousands of Americans from across the country witnessed similar scenes unfold in their communities during this period. Between 1942 and 1946, nearly half a million enemy prisoners of war—over 425,000 German, 50,000 Italian, and 5,000 Japanese—found their way to one of 511 detention camps across the country. The first surge in POWs came with the surrender of Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps in May of 1943; thousands more capitulated to the Allies after the Invasion of Normandy in June of 1944. After arriving by ship at ports-of-entry in New York, Boston, and Norfolk, they traversed the country by train, disembarking at various destinations in nearly every state.

“An estimated 12,000-15,000 of these wartime captives landed in Indiana, where they would live and work at one of nine POW camps across the state. ”

An estimated 12,000-15,000 of these wartime captives landed in Indiana, where they would live and work at one of nine POW camps across the state. Camp Atterbury, located near Edinburgh, Indiana, served as the primary center for POW internment operations, with branch camps operating at Austin, Windfall, Vincennes, Morristown, Eaton, and Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis. Camp Thomas A. Scott (along with the Casad Ordnance Depot), located just outside Fort Wayne, operated under the command of Camp Perry, Ohio. And in the southern part of the state, the Jeffersonville Quartermaster Depot (and nearby Indiana Ordinance Works) functioned as a branch camp of Fort Knox, Kentucky.

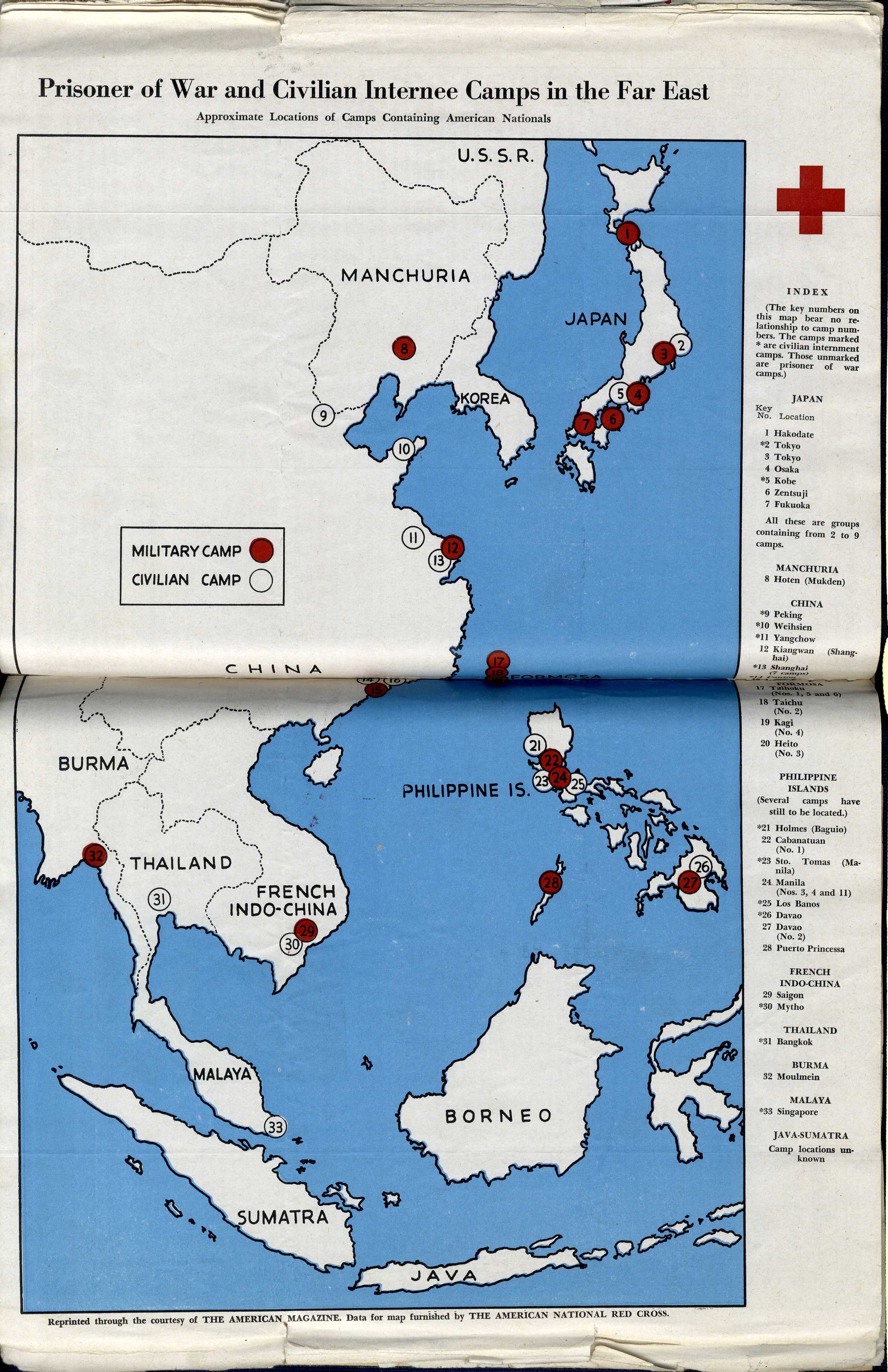

(For more information on these camps, click on the markers in the map below).

This massive influx of war prisoners, unprecedented in U.S. history, created huge demands for a nation and a state already stretched thin in conducting a two-front war. Over 360,000 Hoosier men and women—nearly 10% of the state’s population—served in the armed forces abroad. On the home front, hundreds of industrial firms converted their production efforts to the manufacture of war materials; and the state hosted numerous military installations, including air fields, ordnance depots, training facilities and proving grounds, hospitals, the Army Finance School, and the Atlantic Fleet’s storage depot. Price controls and the rationing of food, clothing, and gasoline further affected civilian life. And despite the persistent labor shortage, agricultural production nearly doubled.

What did Hoosiers think of these uninvited guests? How should they be treated? Did they pose a security threat? What impact would they have on the local economy? The domestic presence of a captive foreign enemy during wartime would seem to have provoked a strong abhorrence—perhaps even violent propensities—from their captors. After all, these prisoners had been responsible for the deaths of thousands of American soldiers abroad—the sons, brothers, uncles, nephews, and cousins of countless Hoosier families.

The presence of enemy POWs in Indiana certainly generated mixed reactions from the local community. Some residents worried about prisoner escapes while others expressed either intrigue or indifference. Most, however, responded with sympathy. One woman, employed at the same canning factory where German prisoners worked in Elwood, Indiana, brought candy bars to the younger ones, recalling that she “felt sorry for them.” Others from the local community empathized with their captive visitors. “They were just people like anyone else,” one woman from Windfall declared, recalling the prisoners who picked tomatoes on the family farm during her youth. “Just like our boys,” noted a man whose father-in-law also relied on POW labor at his farm in Tipton County during the War, “[n]o different.” For others, any sense of reluctance to show compassion quickly dissipated: “Many Italian-American families,” noted a retrospective piece in the Indianapolis Times, “shied away from the Italian prisoners when they first arrived at [Camp] Atterbury. But by the end of the war they were entertaining the prisoners.”

What accounts for this narrative of benevolence? And to what extent did it reflect common public sentiment at the time?

In large part, the answer to these questions lies in the international law obligations to which the United States committed itself as a signatory state to the 1929 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Under the terms of that agreement, the United States—along with 46 other nations—pledged to “mitigate as far as possible, the inevitable rigours [of war] and to alleviate the condition of prisoners of war.” With the outbreak of hostilities during World War II, all major belligerents—with the exception of Japan and the Soviet Union—deposited instruments of ratification or adherence at Geneva. Underlying this commitment was the expectation of reciprocity in the treatment of POWs held by opposing powers, and the risk that derogation from this principle could result in retaliation.

Yet in applying the Geneva Convention, the United States seems to have gone above and beyond the mere letter of the law. Prisoners enjoyed a variety of provisional accommodations: they earned money by working on farms or in canning factories; studied literature, history, business, and economics; played leisurely soccer matches and other games; attended weekly film screenings and church services; and even developed their own musical and theatrical ensembles. Indeed, historians generally agree that POWs in the United States enjoyed a much higher standard of living than those detained in other belligerent nations during World War II. As Robert Doyle points out, “German soldiers jokingly called the ‘PW’ stamped on the backs of their shirts and trousers Pensionierte Wehrmacht, or ‘military retiree,’ meaning they considered themselves put out to pasture.”

As global conflict persisted, however, a war-weary American public became increasingly unsympathetic toward its domestic enemy prisoners. With rationing on the American home front, reports (sometimes of questionable accuracy) that POWs enjoyed a virtually limitless supply of food, clean clothes, and other amenities aroused public indignation. Periodic news accounts of POW Nazism, prison camp escapes, and work strikes provoked even further antipathy. Consequently, accusations of POW “coddling” appeared with greater frequency in the press, ultimately leading to a congressional investigation in 1944. To make matters worse, it became increasingly clear that American POWs abroad enjoyed few, if any, of the comforts afforded their enemy counterparts in the United States. Reports of abuse and inhumane camp conditions revealed gaping disparities in levels of POW treatment.

Thus, with little practical reason to follow the Golden Rule of reciprocity, the United States could easily have abandoned its obligations under the Geneva Convention; remarkably, however, it did not. In renouncing the lex talionis, Americans pursued the moral high ground in adhering to the principles of international humanitarian law.

Of course, there were limits to the American sense of humanity. The tragic irony during this period, as any casual student of history is aware, was the forced removal of over 120,000 Japanese Americans—many of whom were U.S. citizens—to internment, or “relocation,” camps following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. With no charges against them, and with no right to appeal their incarceration, Japanese-American internees lost their personal liberties and most lost their homes, property, and livelihoods. With few exceptions, Americans of German and Italian descent largely avoided a similar fate of mass roundup and incarceration—a clear display of prevailing ideas of race and foreignness.

What does this chapter of history say about the United States? What import, if any, does (or should) it have on modern U.S. policy? In seeking to answer these questions, this story focuses on the State of Indiana. To be sure, the Hoosier experience departed little from that of other communities throughout the nation. However, by examining this period through a lens of state and local activity, the story aims to create an intimate, real-life perspective that broad, general studies often fail to impart.

LEGAL PROTECTIONS DURING WAR AND ARMED CONFLICT: THE PHILOSOPHY AND FRAMEWORK OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW

Despite centuries of diplomacy and countless peace treaties, warfare and armed conflict has continued to plague the global community. In recognizing this reality, nations have agreed to follow certain rules limiting their conduct in war in exchange for the enemy’s agreement to do the same. The Geneva Conventions (which today consist of four treaties and three additional protocols), along with The Hague Conventions, form the basis to this agreement among nations. Known as International Humanitarian Law, or jus in bello, this branch of international law seeks to limit the use of force in armed conflicts by (1) sparing those who do not, or no longer, participate directly in hostilities; and (2) restricting it to the degree necessary to weaken the enemy’s military potential. Underlying this definition are several basic principles: (a) the distinction between civilians and combatants; (b) the prohibition on attacking those hors de combat (i.e., out of action); (c) the prohibition on inflicting unnecessary suffering; (d) necessity; and (e) proportionality.

“International Humanitarian Law [is] the branch of international law limiting the use of violence in armed conflicts by: (a) sparing those who do not or no longer directly participate in hostilities; (b) restricting it to the amount necessary to achieve the aim of the conflict, which—independently of the causes fought for—can only be to weaken the military potential of the enemy.”

The evolutionary process resulting in the codification of these principles reflects an expansive history marked by shifting practices and philosophies in warfare.

ORIGINS & DEVELOPMENT OF JUS IN BELLO

Under ancient laws and customs of warfare, captured enemies enjoyed few if any rights of protected status; they were either killed or—depending on their usefulness—enslaved by the captor. Moreover, little distinction was made between active belligerents and enemy civilians. Among the very few to break with these conventions, Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu raised the novel concept of benevolence toward prisoners of war. In The Art of War, he advocated the idea that “captured soldiers should be kindly treated and kept.”

While enslavement of captured enemy soldiers in Europe declined during the Middle Ages, the practice of ransoming high-ranking military officials persisted into the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth centuries. By then, however, leading political and legal philosophers, such as Hugo Grotius, sought ways to mitigate violence toward prisoners of war. A turning point came in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia. Under its terms, which ended the Thirty Years War in Europe, all prisoners, “without any distinction of the Gown or the Sword,” were to be released and repatriated.

By the mid-eighteenth century, a clear humanitarian movement in international law had begun to take shape, resulting in increasingly better treatment of POWs. In his Law of Nations, first published in 1758 and translated into English two years later, Emerich de Vattel expounded on these emerging principles. “On an enemy’s submitting and laying down his arms,” he wrote, “we cannot with justice take away his life. Thus, in battle, quarter is to be given to those who lay down their arms.” Beyond captured enemy combatants, other groups of people were to be protected from the ordeals of war, including “[w]omen, children, feeble old men, and sick persons.” Clergy, scholars, and “other persons whose mode of life is very remote from military affairs” were likewise to be spared.

Immersed in contemporary law of nations theory, American political leaders during the Revolutionary War applied these principles of international humanitarian law in formulating prisoner of war policy. In October of 1775, a conference of delegates appointed by the Continental Congress agreed that captured enemies were to “be treated as Prisoners of War but with Humanity-And the Allowance of Provisions to be the Rations of the Army. That the Officers being in Pay should supply themselves with Cloaths, their Bills to be taken therefor & the Soldiers furnished as they are now.”

General George Washington, likewise advocating respect for the standards of eighteenth-century warfare, ordered the humane treatment of POWs held by Continental Army. “I shall hold myself,” he wrote in 1782, reluctant to retaliate against British prisoners for atrocities committed against American troops, “obliged to deliver up to the enemy or otherwise punish such of them as shall commit any act which is in the least contrary to the Laws of War.” That same year, when Great Britain failed to supply provisions for its captured soldiers, Congress ordered the Quartermaster General to issue the prisoners “[f]ull rations” of “Bread, Beef or Pork, soap, salt and vinegar.”

The American Revolution impressed upon U.S. political leaders the importance of reciprocity in the treatment of POWs during times of conflict. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce, a peace-time agreement signed with Prussia in 1785, contained important humanitarian provisions for captured enemy combatants. Under Article 24, which sought to “prevent the destruction of prisoners of war,” the contracting parties agreed “that they shall not be confined in dungeons, prison-ships, nor prisons, nor be put into irons, nor bound, nor otherwise restrained in the use of their limbs.” Rather, prisoners were to be “lodged in barracks as roomy & good as are provided by the party in whose power they are for their own troops” and “daily furnished . . . with as many rations; & of the same articles & quality as are allowed by them.”

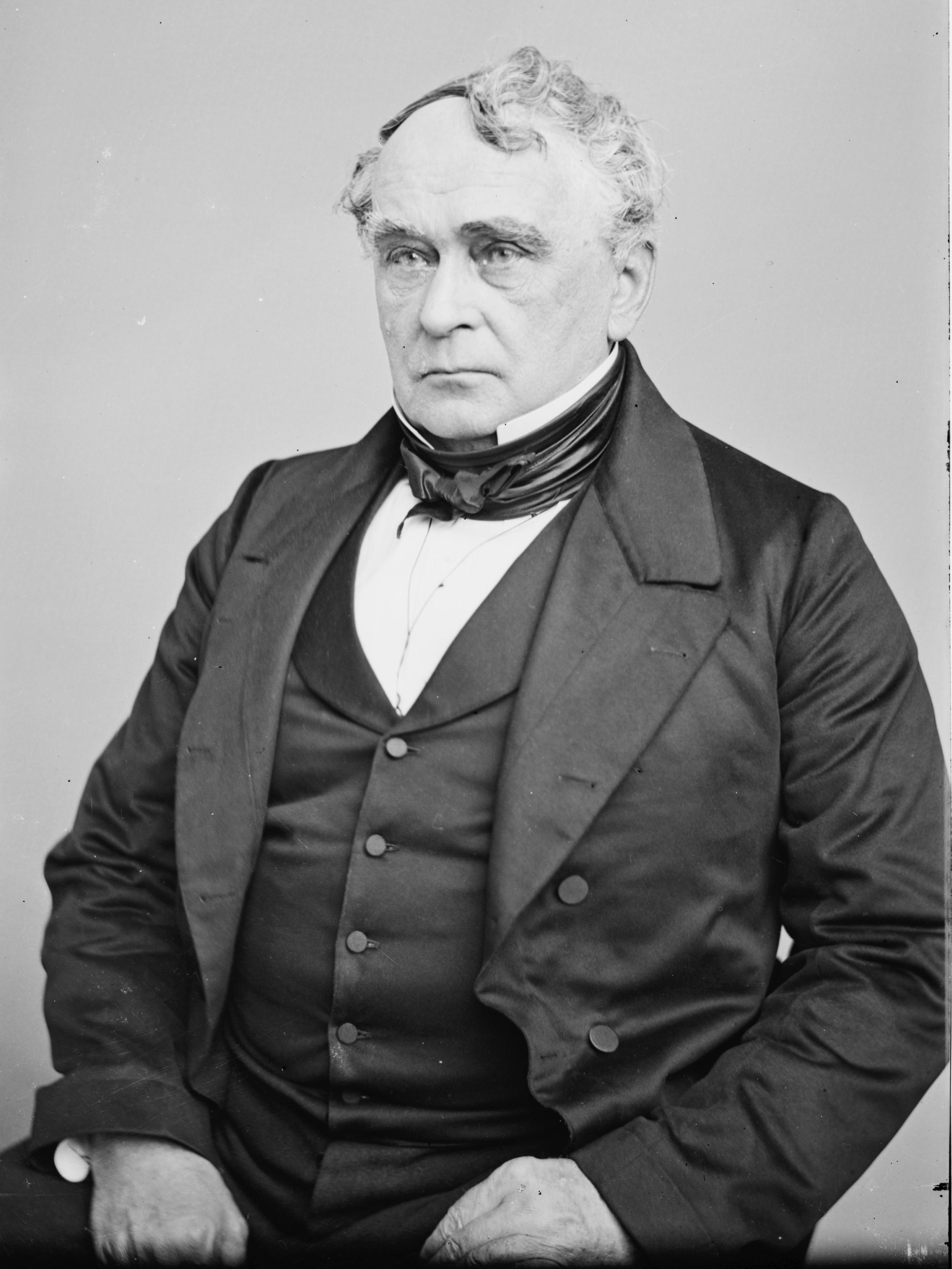

The American Civil War presented the Union with a dilemma over prisoner of war policy; by treating captured Confederate soldiers as traitors, it could deny them the status and rights afforded POWs. Such position, however, risked the likelihood of Confederate retaliation. On the other hand, any formal agreement entered into by the Union conceded sovereign status to the Confederacy.

Union reluctance to negotiate quickly dissipated, however, as early Confederate victories resulted in disproportionately large numbers of Union POWs. In July of 1862, following several failed attempts by both sides at dictating unilateral terms, negotiations concluded with the signing of the Dix-Hill Cartel, an agreement for the parole and exchange of all prisoners based on their military rank. The accord ultimately collapsed, however, when the Confederacy refused to confer POW status on captured black soldiers and their white officers. In response, President Lincoln, on April 24, 1863, promulgated General Orders No. 100, entitled “Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field.” Prepared by German-born legal scholar Francis Lieber, the Instructions, known as the “Lieber Code,” contained several provisions on the humane treatment of POWs. Article 56, for example, stipulated that a “prisoner of war is subject to no punishment for being a public enemy, nor is any revenge wreaked upon him by the intentional infliction of any suffering, or disgrace, by cruel imprisonment, want of food, by mutilation, death, or any other barbarity.” Article 43, an outgrowth of the Emancipation Proclamation, provided that “in a war between the United States and a belligerent which admits of slavery,” persons “held in bondage by that belligerent” would be “immediately entitled to the rights and privileges of a freeman” upon their capture by Union forces or escape from the Confederacy. In reaffirming this policy, President Lincoln wrote that “[t]he law of nations and the usages and customs of war as carried on by civilized powers, permit no distinction as to color in the treatment of prisoners of war as public enemies.”

Yet the large number of prisoners captured on both sides—resulting in hastily organized and poorly supplied detention camps—often led to inadequate provisions. By April of 1862, Camp Morton in Indianapolis had reached nearly five thousand Confederate prisoners. Over a thousand more arrived that summer following the Battle of Shiloh. In the two years that followed, overcrowding and lack of medical care lead to increased sickness and disease among the prisoners. Still, such inhospitable conditions pervaded POW camps on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. Camp Morton, to its credit, had the lowest mortality rate among those within the Union, a feat often attributed to Col. Richard Owen’s humane treatment of the prisoners.

The Lieber Code marked the first attempt among any nation at codifying the laws and customs of war. By influencing the adoption of similar regulations in other nation-states, the measure helped lay the foundation for future efforts at advancing international humanitarian protocols during times of war.

EARLY MULTILATERAL ACCORDS

The violence and bloodshed of the American Civil War and contemporary conflicts in Europe led to a series of multi-lateral conventions designed to mitigate human suffering. The first of these accords resulted largely from the efforts of Henri Dunant, a Swiss philanthropist and founding member of what would become the International Committee of the Red Cross. In August of 1864, Dunant—prompted by the atrocities he had witnessed at the Battle of Solferino five years prior—convened representatives from sixteen nations (including the United States) at Geneva to negotiate and ultimately adopt the Convention for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. The main principles established in the Convention (and preserved in subsequent Geneva Conventions) included relief to the wounded, without distinction of nationality; the neutrality of medical personnel and facilities; and the distinctive emblem of the red cross. The Geneva Convention of 1906, to which the United States was also a party, added twenty-one articles, which included provisions for the burial of the dead, the transmission of information, and the recognition of voluntary aid societies.

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907—intended to expand upon and implement the 1874 Brussels Declaration of principles concerning the laws and customs of war—included several important clauses concerning POWs. For example, Article 6 of the Annex (common to both Conventions) regulated for the first time a belligerent state’s use of prisoner labor, which could “not be excessive” and could have “no connection with the operations of the war.” For its part, the United States—despite French and British encouragement to avoid taking prisoners—upheld the moral high ground in its treatment of POWs. A report from postal censors noted that German “[p]risoners of war under American jurisdiction continue to send home glowing reports of good treatment.” Another described the “treatment accorded them as ‘ritterlich’ (princely), especially the food.”

The Hague Conventions signaled an important step in the development of international humanitarian law. However, the scope of devastation wrought by World War I revealed broad insufficiencies in these international agreements. Article 2 proved especially inadequate by declaring that regulations “do not apply except between Contracting powers, and then only if all the belligerents are parties to the Convention.” The lack of an express mechanism to ensure adherence to Convention terms ultimately forced the negotiation of individual treaties.

THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 1929

In light of the Hague Convention shortcomings, the International Committee of the Red Cross convened in 1921 to propose an exclusive convention on the treatment of prisoners of war. The Committee’s work resulted in a draft convention designed to supplement, rather than replace, the Hague regulations. In receipt of this working document, delegates from forty-seven nations met in Geneva during the spring and early summer of 1929 to recodify international laws relating to prisoners of war. The conference produced two new documents: (1) the Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, and (2) the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick of Armies in the Field.

The Geneva Conventions advanced far beyond previous attempts at codifying international humanitarian law to limit the effects of armed conflict. Each document, to remedy the shortcoming of the Hague Convention, specified that “if, in time of war, a belligerent is not a party to the Convention, its provisions shall, nevertheless, be binding as between all the belligerents who are parties thereto.”

The Prisoner of War Convention expanded on the rules of conduct significantly. Notable innovations consisted of the prohibition of reprisals and collective punishment; the organization of POW labor; the right of neutral authorities to inspect prison camps; and the expanded responsibilities of the captor state to ensure prisoner health and safety. In addition, the Convention required each prisoner to provide only “his true names and rank, or his regimental number.” Prisoners could not be coerced into providing “information regarding the situation in their armed forces or their country.”

WORLD WAR II AND THE APPLICATION OF IHL TO POWS IN INDIANA

On June 4, 1943, U.S. Army headquarters in Washington reported that Camp Atterbury would serve as a permanent internment center for enemy prisoners of war. Just over a month prior to this announcement, the camp had received its first contingent of 767 Italian POWs. By September, that number had grown to 3,000. Colonel John L. Gammell, head of the 1537th Service Unit, served as the commanding officer. “The camp was organized as a regiment of three battalions of five companies each,” writes historian Mary Arbuckle, describing Atterbury’s complex administrative apparatus. “Each battalion was composed of one escort guard company of American soldiers and four companies of prisoners. The prisoners had one regimental, three battalion, and twelve company leaders appointed from their own ranks by the camp commander.”

Above all, effective governance of POW operations depended on strict adherence to the rule of law. “Administration of the camps,” the Camp Crier, Atterbury’s weekly newsletter, announced “in addition to being governed by Army Regulations, must also meet the exacting rules set forth by the Geneva Convention.”

“Administration of the camps, in addition to being governed by Army Regulations, must also meet the exacting rules set forth by the Geneva Convention.”

CONTRACT LABOR

The Geneva Convention consisted of several rules involving POW labor. Under Article 27, belligerent states could employ prisoners, “other than officers and persons of equivalent status,” as workmen, according to their physical fitness and ability. Officers seeking work, however, could hold supervisory positions, “unless they expressly request[ed] a remunerative occupation.” Article 31 prohibited prisoner labor directly connected with wartime operations. This precluded POW employment in the “manufacture or transport of arms or munitions of any kind,” or the “transport of material destined for combatant units.” Article 32 further proscribed “unhealthy or dangerous work.”

Under these provisions, prisoner labor fell into one of two categories: (1) the construction and maintenance of internment camps; and (2) all other types of work, including programs sponsored by the War Department and various state and federal agencies, or contract work in the private sector, typically in agriculture or canning factories.

Contract labor in the private sector proved enormously successful, due to the critical labor shortage throughout the United States, particularly in the agricultural industry. On May 19, 1943, Col. Welton Modisette, post commander at Camp Atterbury, announced that Italian POWs were available for agricultural labor within a twenty-five mile radius of the camp. Potential employers were to send requests for POW labor to the local office of the War Manpower Commission (chaired by former Indiana Governor Paul V. McNutt). After confirming the unavailability of civilian labor, the WMC issued a certification of need to a camp contract officer who, in turn, drafted an agreement between the government and the employer.

A standard contract for POW labor stipulated the type and amount of work to be done, the location of the farm or factory, an estimate of working hours, and the amount of pay. The War Department was “responsible for the supervision of guarding, rationing, clothing, quartering, transporting, and providing medical attention” for all prisoners. However, “the cost of rationing and transporting” was “borne by the Contractor.” The agreement further required the employer to supervise prisoner labor; maintain “clean and sanitary” premises; “furnish the materials, equipment, tools and other articles or facilities necessary in the performance of the work;” and “comply with all applicable Workmen’s Compensation Laws.” Governing law provisions expressly referenced the “requirements and prohibitions of the Geneva Convention of July 27, 1929.” Standard contracts also contained a dispute resolution clause, specifying that any disagreement be “decided by the Contracting Officer.” Contractors could appeal these decisions “in writing to the Secretary of War,” whose written decision would be “final and conclusive upon the parties.”

A schedule to the contract specified the amount and manner of payment to the government. Prisoner earnings reflected the prevailing local wage; however, they kept only an 80-cent per diem allowance (in addition to a flat allowance of ten cents a day from the U.S. Government) up to $13 a month in coupons exchangeable at camp canteens where they could purchase sundry goods. Any additional amount earned was kept in a trust account until prisoner repatriation.

Despite the economic benefits of POW labor, American labor unions often protested that it inhibited opportunities for civilians. Aware of these concerns, the War Manpower Commission certified that POWs not only received the local prevailing wage, but also had the same working conditions as civilian labor. Occasionally, employers ran afoul of these requirements. Morgan Packing Company, located in Austin, Indiana, employed over 1,500 German and Italian prisoners from 1944 to 1946. Morgan’s contract called for the payment of 40 cents per hour, plus overtime, and covered only common, or unskilled, labor at its food canning facility. However, during an inspection of the Morgan plant in September of 1945, WMC officers discovered approximately twenty-five POWs engaged in new construction, bricklaying, and scaffolding assembly. An additional forty prisoners were mixing concrete and paving driveways and parking areas. Inspection officers quickly suspended these operations, informing the company that it would first need to obtain a certification of need for skilled labor.

SECURITY & DISCIPLINE

The Geneva Convention provided little guidance on dealing with insubordinate prisoners for failing to work. Article 32 simply stated that “[c]onditions of work shall not be rendered more arduous by disciplinary measures.” Article 55, in turn, permitted restrictions on food “to prisoners of war undergoing disciplinary punishment.” To help clarify these rules, the War Department issued guidelines on “Administrative and Disciplinary Measures” in October of 1943. For the commanding officer to effectively “utilize and control prisoner of war labor and to administer and maintain his camp in a satisfactory manner,” the guidelines encouraged “preventive remedies wherever possible.” Permissible administrative measures included verbal reprimands; withholding of certain privileges, “including restrictions on diet;” and “[d]iscontinuance of pay and allowances.”

According to a report from the House Committee on Military Affairs in 1944, there had been “no courts martial of prisoners at Camp Atterbury, but 141 Italians and 19 Germans ha[d] been summarily disciplined for minor infractions of the rules and regulations.”

In September of that year, German prisoners at Camp Windfall—“[o]ne thousand” of them, according to the Tipton Tribune—were “placed on bread and water rations . . . following their refusal to work in county canning plants and tomato fields.” And at Fort Benjamin Harrison, “[f]ifteen others [were] summarily disciplined, nine for refusing to perform work assigned them in connection with sewage disposal, and six for arranging two-toned shingles on the roof of the Billings General Hospital in the form of a swastika.” Historian Arnold Krammer notes that the “authorities [later] ordered the six men to return to the roof and rearrange the shingles, after which . . . they were all placed on a diet of bread and water for a period of 14 days.”

In an attempt to mitigate camp violence, military officials segregated the most hardcore of Nazi and Fascist sympathizers from the general POW population. Most prisoners, however, kept quiet as to their ideological views. Anti-Nazi prisoners feared trial by kangaroo court or, with rumors of German spies keeping lists of traitors, reprisals against family members back home. Although no murders appear to have taken place at any of Indiana’s POW camps, political volatility and ideological extremism occasionally led to violence and disruption of camp operations. According to the roster of POW internees at Camp Atterbury, Michele Carrubba, an Italian corporal and self-declared pro-Fascist, “[a]ttacked the Italian Company Leader” for his pro-Ally views and “[t]hreatened revenge on all US personnel.” Rinaldo Bonvini, another pro-Fascist POW, was “one of a number of agitators who signed their names to a pledge of loyalty bearing the Swastika, Rising Sun and Fascist emblems.”

The possibility of prisoner escapes generated a certain level of fear among local communities. Although infrequent—considering their conspicuous appearance and lack of English proficiency—attempted escapes were not unheard of. At Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis, one POW had made such an attempt but was “recaptured within an hour.” Krammer writes of an escapee from Camp Atterbury “captured by an eight-year-old boy, who, playing with a toy pistol, ordered an imaginary adversary to come out of an abandoned shack near the boy’s home in Columbus, Indiana.”

Two German POWs escaped from Camp Austin one night in October of 1943. They were captured the following evening in a field near Brownstown. “The prisoners,” according to the Indianapolis Star, “. . . were believed to have secreted themselves in a truck loaded with canned goods which left the [Morgan Packing Company plant]” late Friday for Bedford.

Another disciplinary problem that invariably arose involved prisoner fraternization with women. As a result, employers often took precautionary measures. At Camp Austin, for example, guards attempted “a physical separation, if possible, when PWs worked next to women.”

Overall, it seems, instances of prisoner recalcitrance—and thus the need for disciplinary measures—remained relatively low in Indiana, at least among the Italians. In February of 1944, Dr. Benjamin Spiro, representing the Legation of Switzerland, Department of Italian Interests, reported that “discipline at [Camp Atterbury] is good, but not as strict as it might be.” He continued:

There have been no court martials and few punishments. The entire camp has been placed on a limited parole basis. That is to say, each of the prisoners is issued a limited parole card which permits him to move freely in and around the camp within certain limits. The general atmosphere of the camp is good. The morale of the prisoners is high. . . . The prisoners are generally well-behaved. The parole system seems to be working unusually well.

In June of 1945, following the arrival of German POWs at Camp Atterbury, the U.S. Department of State reported that, “disciplinary action covering the three months of November, December and January shows a total of 41, who were given from three to 30 days sentence, usually on restricted diet. The principal misdemeanors were refusal to work, unsatisfactory work, insubordination, unauthorized possession of United States Government property, theft, and sabotage.” And “[d]uring the period from December 6, 1944 to March 15, 1945 inclusive, there were a total of 81 cases of disciplinary punishment at this camp. Most of these were single cases and the sentence was usually seven to 14 days hard labor without pay.” The report went on the describe specific instances of disciplinary action:

[O]n February 7, a group of 20 prisoners refused to unload a railway car when on prescribed work detail. They were sentenced to seven days on bread and water. On February 28, four prisoners refused to give their names to the work foreman while on prescribed work detail. Their sentence was seven days at hard labor, no pay, with full rations. On March 15, four prisoners were charged with laxity on “Classification Warehouse Work” detail. They were sentenced to three days hard labor without pay, on full rations.

RECREATION, RELIGION & EDUCATION

Under Article 16 of the Geneva Convention, prisoners enjoyed “complete freedom in the performance of their religious duties, including attendance at the services of their faith.” Prisoner religious personnel, regardless of their denomination, were “allowed freely to minister to their co-religionists.” In the absence of captive clergy, the U.S. Army appointed local religious personnel to minister services, often in the prisoners’ native language. At Fort Benjamin Harrison “[a] German-speaking Lutheran pastor from Indianapolis [was] permitted to enter the stockade every Sunday morning and preach to the prisoners.” Apparently, however, “no more than one-fifth of them attend[ed] the services.

Construction planning for prisoner camps initially called for the inclusion of chapels. However, many of the detention sites lacked suitable structures. Some prisoners found innovative solutions to this problem. Italian POWs at Camp Atterbury received permission to construct a small chapel. According to one source, “the prisoners used leftover brick and stucco to construct the building. Inside, they used berries, flowers—even blood, it’s rumored—to create pigments for hand-painted frescos of religious figures: cherubs, Madonna, angels, the dove of peace, and on the ceiling, the eye of God." The chapel opened for service on Sunday, October 17, 1943, with a mass and dedication led by Amleto Giovanni Cicognani, the Vatican’s apostolic delegate to the United States. The ceremony followed with a performance by a fourty-five piece POW orchestra.

Article 17 of the Geneva Convention required, “[s]o far as possible,” belligerent captors to “encourage intellectual diversions and sports organized by prisoners of war.” Under these terms, POWs engaged in a variety of sports and often organized athletic events. At Fort Benjamin Harrison, prisoners were “permitted to play soccer and other games” in a nearby “uninclosed [sic] athletic field.”

“Life is not all work and no play for the prisoners,” a reporter from the Franklin Evening Star noted during a visit to Camp Atterbury in June of 1943. The POWs had access to a large recreational area, which included “facilities for three soccer fields, six volley ball courts, one boxing ring, three boccie [sic] fields, and [outdoor] gymnasium.” At Camp Atterbury, in August of 1943, a representative of the International Red Cross “watched a [soccer] match which showed that the men [were] well versed in the game and in good physical condition. During the period between halves, the military band played Italian marches.” In addition to holding “[c]ompetitive games,” the Italian prisoners performed “a stage play [and] a philharmonic concert.”

At Camp Austin, the YMCA and German Red Cross provided POWs with books and phonographs. A theater there presented weekly films and served as a stage for a twenty-two-piece POW orchestra. Prisoners also had access to a small recreation field to play soccer, handball and volleyball games. And religious services, both Catholic and Protestant, took place on Sundays.

In addition to books, newspapers, and other reading materials (all censored, of course), prisoners took classes, in which they studied a variety of subjects. Camp Austin, for example, offered evening courses on agriculture, mathematics, stenography, and the linguistic arts.

Most classes consisted of informal, weekly discussions led by members of the local community; others provided more formal, rigorous instruction, with courses taught by qualified teachers. These formal programs included exams and often led to course credit through cooperating academic institutions in both the United States and Germany. Several American universities offered correspondence programs of study. Through Indiana University’s Extension Division program, prisoners from camps throughout the United States—including Arkansas, Tennessee, Kansas, Idaho, and Louisiana—studied law, sociology, business, hygiene, physiology, economics, geography, English, and communications philosophy.

Beyond promoting the mere leisurely pursuit of academic study, the POW education program in the United States—known as “intellectual diversion programs”—was an attempt to politically reorient the prisoners. Camp Atterbury, according to historian Dorothy Riker, “conducted an intellectual diversion program which included over 35 courses of academic instruction, emphasis being placed on principles of democracy.” Some of the prisoners even “prepared and printed a textbook on democracy.” Because these efforts could be seen as an attempt by U.S. authorities to indoctrinate or denationalize the prisoners, and because the Geneva Convention prohibited such efforts, details of the program were highly classified. Shortly after the end of the War, the Indianapolis Star, wrote that Indiana University was “one of 100 American colleges and universities which . . . attempt[ed] to remove some of the Nazi poison from the thinking of 370,000 German prisoners of war in this country.”

CAMP INSPECTIONS

To ensure adherence to its provisions, the Geneva Conventions established a de facto diplomatic framework, allowing belligerent states to learn of prisoner conditions and, if necessary, engage in indirect negotiations with the enemy. To accomplish this, Article 86 encouraged belligerent states to “appoint delegates from among their own nationals or from among the nationals of other neutral Powers” who would be “permitted to go to any place, without exception, where prisoners of war are interned.”

Prisoner camps in Indiana received periodic visits by representatives of the International Red Cross and YMCA, delegations from neutral state powers, and officials from the State Department, the Provost Marshal General’s office, the House Military Affairs Committee, and the Office of the President of the United States.

Naturally, governmental authorities were highly sensitive to these inspections; any findings of POW mistreatment would likely result in retaliation against American prisoners abroad. Estimates vary, but close to 130,000 American POWs fell into enemy hands over the course of World War II. Among them was Bruce Gribben of Indianapolis, a flight officer in the Army Air Corps who was shot down and captured by German fighters off the coast of Salerno, Italy, on August 22, 1943. In a letter written from a German a prison camp less than a month after his capture, Gribben assured his family back home that he was “well and warm,” although in need of toiletries, various articles of clothing, and his bible. So he asked that they “[g]o to the Red Cross and find out what [they could] send.” The Red Cross, he emphasized, was “the only thing that [kept the POWs] going.” Gribben would spend nearly two years in German prison camps before his liberation on April 29, 1945.

In reporting on its wartime activities, the ICRC described using the following methods in conducting a typical POW camp inspection:

After getting information from the camp leader and camp authorities, [the ICRC representative] made a careful inspection of the various buildings: sleeping quarters, cook-houses, mess halls, sick wards, rooms for games or recreation, latrines, washhouses, etc. He questioned any PW whom he met there. . . . He asked for the bills of fare, and checked the stock of foodstuffs and store of medicaments. . . . He had long talks with the chaplains of the different communities, with the camp leader and finally, with all PW who asked to be heard. All complaints were listened to and forwarded.

By gathering this information, the ICRC inspector “could thus carry away from his visits a complete picture: equipment of the camp, discipline, relations between the authorities and the men, etc.”

On August 29, 1943, following an inspection of Camp Atterbury, the ICRC reported that “[t]he camp leaves a very good impression and the Camp Commander does everything he can for the prisoners. The latter appreciate his services and collaborate with him fully.” A subsequent inspection report on March 24, 1944, concluded that “[t]he prisoners enjoy all the advantages and all the amusements that it is possible to grant them. Their morale is good.” In confirming these opinions, the State Department, following an inspection on June 1, 1945, made the following observations:

Atterbury is an exceptionally well administrated prisoner of war camp. The commanding officer very plainly has the confidence and close cooperation of all his assistants, who in turn appear to have been able to get unusually satisfactory services from the prisoners themselves, whether in contract farm work or at the base camp and the prisoner of war camp itself.

Despite these glowing reports of Camp Atterbury, other POW camps in Indiana failed to measure up. Following an inspection of Camp Austin on December 1, 1944, Swiss delegates declared the detention site “most primitive.” The inspectors noted in particular the lack of winterized tents for all POWs, as well as the unsanitary condition of prisoner latrines and bathing facilities. Additionally, the lack of a canteen and mess hall (although under construction) forced prisoners to eat in their tents. Inspectors expressed particular concern with Geneva Convention violations when they learned of the camp’s failure to report the alleged bayoneting of several prisoners. Whether revelation of these facts resulted in diplomatic tensions or retaliatory measures against American POWs overseas is unclear; fortunately, however, the Swiss Legation found conditions at Camp Austin had improved significantly during a return visit in May of 1945.

"EDEN FOR ENEMY PRISONERS": RESPONDING TO DOMESTIC CHARGES OF POW "CODDLING"

In November of 1944, the congressional House Committee on Military Affairs conducted an investigation into the national war effort, responding to “reports in some communities adjacent to detention camps” that, despite wartime rationing for the rest of the civilian population, “enemy prisoners of war were being granted too many privileges and liberties.” In preparing its assessment, the Committee conducted a survey of several POW camps. At Camp Atterbury, the report noted, “[t]reatment accorded the prisoners has been in conformity with the provisions of the Geneva Convention of 1929. They have not been dealt with harshly, neither have they been coddled. There have been no dances or any parties of any kind for them. Civilians have not been permitted to visit them inside the stockade.” And “[a]s to the manner prisoners of war have been handled at Fort Benjamin Harrison,” the Committee found “no evidence of any criticism or resentment . . . among the civilian population of Indianapolis.”

Much of the criticism to which the Committee responded had appeared in the national press. An editorial published in the Indianapolis Star on February 4, 1944, entitled “Eden for Enemy Prisoners,” seems to have captured the prevailing public sentiment:

The expectation expressed by a well-educated German after capture near Rome of an easy carefree life in the United States as a prisoner of war probably reflects the general view of our enemies. His estimate of prospects was reported in a press dispatch from the Italian front. The Nazi said the general belief existed among his forces that they would live off the fat of the land in America, wandering around towns as trustees.

Such was the conviction and hope of most Italian prisoners in the later stages of their part in the war. Men taken in North Africa were said to have gloated over the prospect of transfer to the United States. This attitude prevailed among Italians held at Camp Atterbury. Many of them expressed the hope of remaining in the country after the war.

While acknowledging that prisoners “should not be abused,” the editorial concluded that “any violation of rules should result in punishment. Our enemies should be disillusioned of ideas that the United States is a paradise for prisoners.”

Then, in late December of 1944, news reached the United States that members of a German combat unit massacred over eighty American POWs near Malmedy, Belgium. Reports would later surface on the mistreatment afforded other American POWs by German soldiers. “It was our misfortune to have sadistic and fanatical guards,” wrote Pfc. Kurt Vonnegut to his family on May 29, 1945, following his liberation from the Dresden work camp Schlachthaus Fünf. “We were refused medical attention and clothing[.] We were given long hours at extremely hard labor. Our food ration was two-hundred-and-fifty grams of black bread and one pint of unseasoned potato soup each day.”

“It was our misfortune to have sadistic and fanatical guards.”

The Allied liberation of Nazi death camps at Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchewald, Bergen Belsen, and other sites in 1945 revealed the extent to which Germany engaged in war crimes against soldiers and civilians alike. Now, with no practical reason to follow the Geneva Conventions, public criticism of POW treatment in the United States gave way to calls for retribution against the enemy captives on the home front.

Colonel Gammell, in response, persuaded journalist Mary Bostwick to visit the camp, “with free access to everything and anything affecting the camp administration.” Her report, published in the Indianapolis Star on April 8, 1945, discredited the idea that German POWs at the camp were “leading a carefree country club existence.” “On the contrary,” she wrote,

they work hard 10 hours a day, they not only pay their own way, but their work on farms, in canning factories, etc., will put about $1,500,000 in the United States Treasury this year, they do a great many of the chores around Camp Atterbury that the American soldier never has been particularly keen about doing, and the fact that they are treated fairly and humanely has more than returned dividends in the treatment of American prisoners of war in Germany.

Bostwick goes on to remind readers that “the treatment accorded the German PWs is that prescribed by the Geneva Convention, that the Geneva Convention is law, and that the United States Army is administering it.” The POW detention facility at Camp Atterbury, she added, “is run in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, under firm military discipline and it has the reputation of being one of the model PW camps in the country.”

In June of 1945, responding to growing criticism directed at the War Department’s handling of enemy POWs, the House Committee on Military Affairs issued a second report. “The criticism arises,” the report noted, “. . . largely from a lack of understanding of the objectives sought, as well as from a misconception of the basic provisions of the Geneva Convention and applicable international law on which the prisoner-of-war program is of necessity based.” While acknowledging that “American prisoners of war [had] been badly treated in some places,” the Committee held steadfast in its support of military obligations under the Geneva Conventions. For one thing, adherence to the rule of law had “already paid large dividends.” German soldiers, upon receiving reports from Red Cross authorities that U.S. forces were treating prisoners fairly, became “willing, even eager, to surrender.” Had such reports been fabricated, “victory would have been slower and harder, and a far greater number of Americans killed.”

Yet perhaps the most compelling reason for U.S. commitment to the rule of law—one that transcended the principles of the Geneva Convention—emerged from the Committee’s appeal to the nation’s moral and ethical code:

For us to treat with undue harshness the Germans in our hands would be to adopt the Nazi principle of hostages. The particular men held by us are not necessarily the ones who ill-treated our men in German prison camps. To punish one man for what another has done is not an American principle.

In the end, these words would carry the day. Despite calls for retaliation, and strong criticism of U.S. military policy, the rule of law would ultimately prevail.

“For us to treat with undue harshness the Germans in our hands would be to adopt the Nazi principle of hostages. The particular men held by us are not necessarily the ones who ill-treated our men in German prison camps. To punish one man for what another has done is not an American principle.”

CONCLUSION

World War II represented America’s finest hour in its treatment of enemy POWs. Problems certainly arose in the process, leading to occasional failures in upholding the rule of law; however, as Robert Doyle observes, “[i]f the Americans failed to attain the moral high ground during this era, it was through sins of omission rather than commission.” Overall, the United States exceeded its obligations under the Geneva Conventions, maintaining its historical reputation among the global community as a torchbearer in advancing the principles of international humanitarian law, a status for which the nation enjoyed wide recognition—domestically and abroad—for most of the twentieth century.

The experience in Indiana exemplified the nation’s model conduct towards its enemy captives, the effects of which cannot be overemphasized. In a “special edition” of Lagerstimme, Camp Atterbury’s POW newsletter, the comments of former German prisoners are especially revealing:

With this modest mark of appreciation the prisoners of war wish to express their gratitude to the officers of the camp, and to Colonel Gammel whose relentless consideration of our welfare, wise leadership, and fair, just and strict administration effected such an unhampered and successful cooperation during two years of our captivity in the United States.

The Commanding Officer may rest assured that we shall depart from this camp with the best impressions of the United States Army and the country it represents. These years in America will certainly exert an important influence upon the future shape of our homeland which will undoubtedly be the best tribute to the activities of the Commanding Officer.

Despite the circumstances of their internment, the overall positive experience of these prisoners, like thousands of others in the United States, impressed upon them a strong sense of admiration for the American way of life.

MOVING FORWARD, LOOKING BACK

At the conclusion of the War, the POW program in the United States officially came to a close and the gradual process of repatriation began. With the dismantling of prison camps and the passage of time, this chapter in American history gradually receded from public memory. Today, save for the occasional chapel or small cemetery, the physical landscape furnishes little evidence of where these prisoners once lived, labored, worshipped, played, and mourned their deceased compatriots.

And yet, with each passing generation, the narrative persists, constantly evolving to elicit complex moral and legal questions that Hoosiers and other Americans continue to wrestle with. What constitutes an act of war or armed conflict? Does IHL entitle “irregular” combatants—such as spies, saboteurs, guerrillas, mercenaries, or terrorists—to POW status? If not, how should these combatants be treated? Are they entitled to any protections under the law? Is torture permissible in order to acquire important military information?

In 1949, as the world continued rebuilding from the ruins of World War II, state delegates convened to assess the effectiveness of the Geneva Conventions in mitigating the atrocities of armed conflict. The conference resulted in extensive revisions to the existing treaties and the implementation of two additional conventions: one to protect wounded, sick, and shipwrecked military personnel at sea during war; and the other to protect civilians, including those in occupied territory—a direct response to the Nazi atrocities committed against Jewish peoples and other minority groups. Changes to the Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War included expanded categories of persons entitled to POW status, and refined definitions of the conditions and places of captivity, especially in relation to prisoner labor and judicial relief in cases of prosecution. All four of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, to which every nation is a party, remain in force today.

Subsequent developments in the character of armed conflict—including technological advancements in weaponry and the growing use of guerrilla warfare—called for supplementary humanitarian protections. The Additional Protocols of 1977 are the culmination of efforts to adapt the laws of war to contemporary needs. Additional Protocol I (AP I) expanded the category of “lawful belligerents” and requires combatants to use all practical safeguards to avoid incidental loss of life. Additional Protocol II (AP II), which deals with non-international armed conflicts, aims to extend the essential rules of international humanitarian law to internal (or “civil”) wars. Both measures apply to civilians and combatants alike and impose greater obligations on warring parties to distinguish between the two. A third additional protocol (AP III), adopted in 2005, established a new emblem, the red crystal, which corresponds in status to the red cross and red crescent. The United States, while a state party to AP III, has not ratified APs I or II.

Despite these advances in IHL, the lack of precision in defining war—seldom a state of officially declared armed conflict—raises difficult questions over the context in which the Geneva Conventions apply. In seeking to avoid interpretive ambiguities, Common Article 2 (so called because each of the four Geneva Conventions shares the same provision) states that “the present Convention shall apply to all cases of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of the High Contracting Parties, even if the state of war is not recognized by one of them.” But what if one state refuses to acknowledge an opposing belligerent as a legitimate party to the conflict?

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, precipitated an entirely new paradigm of international armed conflict, bringing with it conflicting ideas of how humanitarian law should apply. Unlike the German, Italian, and Japanese POWs held by U.S. military forces during World War II, the nation’s new captive enemy in the global “War on Terror” would have no interaction with the American public and only vaguely-defined protections under the law.

In November of 2001, President George W. Bush—in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief and by authority of joint resolution by Congress—authorized the establishment of extraterritorial military commissions to try non-U.S. citizen enemy combatants suspected of terrorism. Efforts to deprive suspected enemy combatants of legal protections soon followed. First, by sending al-Qaeda and Taliban detainees to the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the administration attempted to circumvent the jurisdiction of the federal courts. The result, according to Indiana Supreme Court Justice Steven H. David, the former Chief Defense Counsel to the Office of Military Commissions at Guantánamo Bay, was “a Constitutional no-man’s land of military tribunals and commissions—a veritable black hole of judicial precedent and construction.”

In classifying members of al-Qaeda as “unlawful combatants,” the Bush Administration interpreted provisions of the Geneva Convention so as to preclude detainees from certain legal protections. Under Article 4, members of regular (or internationally-recognized) armed forces, including militias and volunteer corps serving as part of the armed forces, are entitled to POW status. To qualify for the same status, so-called “irregular” combatants must (a) “be commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates,” (b) wear uniforms with “a fixed distinctive emblem recognizable at a distance,” (c) “carry arms openly,” and (d) comply with the “laws and customs of war.”

Terrorist organizations such as al-Qaeda clearly fall short of these criteria: they rely on civilian cover, rather than distinctive emblems or military uniforms; they fail to carry arms openly, thus concealing their intent to use force; and, by attacking civilian groups, they exceed the boundaries of accepted laws and customs of war.

However, if history is any guide, there is no firm precedent for categorically denying POW status on the grounds that irregular combatants failed to comply completely with these provisions. To the contrary, the United States has long interpreted Article 4 liberally, not only in according POW status to irregular enemy combatants, but also in supporting such status for irregular allied forces, and in objecting to adversarial belligerents’ denial of such status for U.S. military personnel captured abroad.

Historical practice aside, the Geneva Convention provides all enemy detainees with basic guarantees of humane treatment, including protections against torture and humiliation. Common Article 3, which applies in cases of armed conflict “not of an international character,” ensures minimum standards of protection for all persons in enemy hands, regardless of distinction in status. Belligerent acts “prohibited at any time and in any place” include, among others, “violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture.”

Despite assurances of humane treatment, the absence of express legal restraints ultimately resulted in the torture and abuse of prisoners at the hands of untrained military police and U.S. intelligence officers at detention facilities in Afghanistan, Iraq, Guantánamo Bay, and other “black sites” (or secret prisons) throughout the world.

On December 9, 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee released its report on the CIA’s detention and interrogation program for detained suspected terrorists. The report concluded that the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” techniques—which involved waterboarding, sexual violence, the use of coffin-size confinement boxes, and other brutal methods unfit for description—not only thwarted effective intelligence gathering in the interests of national security, but also ran counter to the moral values of the nation. As observed by Dianne Feinstein, the Senate Intelligence Committee’s Chair,

The major lesson of this report is that regardless of the pressures and the need to act, the Intelligence Community’s actions must always reflect who we are as a nation, and adhere to our laws and standards. It is precisely at these times of national crisis that our government must be guided by the lessons of our history and subject decisions to internal and external review.

With the report’s completion, the Committee Chair expressed optimism “that U.S. policy will never again allow for secret indefinite detention and the use of coercive interrogations.” Whether the United States recommits itself to the prohibition of torture, as “enshrined in legislation,” is a question that has yet to be decided.

“The major lesson of this report is that regardless of the pressures and the need to act, the Intelligence Community’s actions must always reflect who we are as a nation, and adhere to our laws and standards. It is precisely at these times of national crisis that our government must be guided by the lessons of our history and subject decisions to internal and external review.”

****

In looking forward, perhaps it's worth revisiting an earlier chapter from Indiana legal history. During the American Civil War, threats of a Confederate fifth column in the North—especially in the border states of the Midwest—resulted in extraordinary restrictions on civil liberties by the Lincoln Administration, including the imposition of martial law, suspension of habeas corpus, and the use of military tribunals for civilians.

On October 5, 1864, the U.S. government arrested Lambdin P. Milligan, a civilian and citizen of the State of Indiana, on charges of treason, conspiracy to free Southern prisoners of war, inciting insurrection, violating the laws of war, and other crimes. Milligan and his alleged co-conspirators were tried and convicted by a military tribunal, and sentenced to death. Milligan filed a petition for habeas corpus, challenging the military tribunal’s jurisdiction over him as a civilian residing outside the theatre of war. In Ex parte Milligan, the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly found that a citizen civilian could not be tried by a military court in jurisdictions where civil courts are available. In writing for the majority of the Court, Justice David Davis famously pronounced that

[t]he Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times, and under all circumstances. No doctrine, involving more pernicious consequences, was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism, but the theory of necessity on which it is based is false.

Although often hailed as a landmark decision in protecting civil liberties, Milligan’s authority gradually subsided under the weight of subsequent case law. Ex parte Quirin involved the trial and conviction of Nazi saboteurs—two of whom were American citizen expatriates—by a U.S. military tribunal for conspiring, under cloak of civilian dress, to destroy American war facilities during World War II. Citing Milligan, they petitioned for habeas corpus and sought trial by civilian court. In rejecting their petition, the U.S. Supreme Court distinguished between the “armed forces and the peaceful populations of belligerent nations and also between those who are lawful and unlawful combatants.” The Nazi saboteurs, as members of an enemy state, fell into this latter category and, in violating the laws of war, were “subject to trial and punishment by military tribunals.” Milligan, on the other hand, “not being a part of or associated with the armed forces of the enemy, was a non-belligerent, not subject to the law of war save as . . . martial law might be constitutionally established.”

Despite the eroding effects of intervening precedent, Milligan remains an important decision in the context of the War on Terror: while there has been little clarification by the courts of the legal issues surrounding the detention of unlawful combatants, the case, as one prominent legal scholar puts it, serves as a “precedential counterweight to claims of unlimited government authority in wartime.”

There is no doubt that acts of international terrorism plague the global community. And those guilty of violating the laws of war must be held accountable for their crimes. However, the use of torture and the selective compliance with international humanitarian law risks undermining America’s credibility abroad, threatens to alienate our wartime allies, and increases the likelihood of enemy retaliation against members of the U.S. armed forces. Moreover, the decision to extend legal protections to the enemy combatant—whether under the U.S. Constitution or the Geneva Conventions—places no barrier in the administration of justice.

In the end, Americans must decide if the detainees in the global War on Terror pose any greater threat to the United States than Nazi saboteurs during World War II, a Confederate fifth column in the north during the Civil War, or even individuals such as Timothy McVeigh, all of whom had received the full protection of the law.

Special thanks to my son Emilio for inspiring me to work on this story, sharing an appreciation for the power of storytelling, and assistance in the early stages of research. And a shout out to my cousin Carrie Schwier, archivist at Indiana University in Bloomington, for helping locate records on POWs enrolled in IU's Extension Division program during the War.

This post was last updated on September 6, 2015, with an extended conclusion, embedded links, and new media. To download a copy of this note in its original form with extended commentary and footnotes, click here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Borelli, Sylvia. Casting Light on the Legal Black Hole: International Law and Detentions Abroad in the “War on Terror,” 87 Int’l Rev. Red Cross 39 (2005).

Bradley, Curtis A. The Military Commission Act, Habeus Corpus, and the Geneva Conventions, 101 Am. J. Int’l L. 322 (2007).

Curtis A. The Story of Ex Parte Milligan: Military Trials, Enemy Combatants, and Congressional Authorization.

David, Steven H. Ex Parte Milligan and the Detainees at Guantanamo Bay: A Legacy Lost, 109 Ind. Mag. Hist. 380 (2013).

Elsea, Jennifer K., Cong. Research Serv. RL31367, Treatment of “Battlefield Detainees” in the War on Terrorism (2007).

Elsea, Jennifer K., Michael John Garcia, Cong. Research Serv. R42143, Wartime Detention Provisions in Recent Defense Authorization Legislation (2015).

Flory, William S. Prisoners of War: A Study in the Development of International Law (1942).

Flynn, Eleanor C. The Geneva Convention on Treatment of Prisoners of War, G.W. L. Rev. 505.

Heisler, Barbara Schmitter. Returning to America: German Prisoners of War and the American Experience, 31 German Stud. Rev. 537 (2008).

Indiana Landmarks. Comfort in a Time of War: Camp Atterbury’s POW Chapel, Hidden Gems (Sept. 25, 2014).

Indiana University, McKinney School of Law, Program in Int'l Human Rights Law. Gitmo Observer.

Inter-Am. Comm’n H.R. Towards the Closure of Guantanamo, OAS/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 20/15 (June 3, 2015).

International Committee of The Red Cross. Report of The International Committee of The Red Cross on Its Activities During The Second World War (September 1, 1939 — June 30, 1947), Vols. 1-3.

Keefer, Louis E. Italian Prisoners of War in America, 1942-1946: Captives or Allies? (1992).

Letters from Fighting Hoosiers (Howard Peckham & Shirley A. Snyder, eds. 1948).

Lewis, George, and John Mewha. History of Prisoner of War Utilization by the United States Army, 1776-1945 (1955).

Mofidi, Manooher & Amy E. Eckert. “Unlawful Combatants” or “Prisoners of War”: The Law and Politics of Labels, 36 Cornell Int’l L.J. 59 (2003).

Mason, John Brown. German Prisoners of War in the United States, 39 Am. J. Int’l Law 198 (1945).

Nazi Summer Camp. RadioLab (May 22, 2015).

Scheinkman, Andrei, et al. The Guantánamo Docket, N.Y. Times.

Sullivan, Jr., Justice Frank. Indianapolis Judges and Lawyers Dramatize Ex Parte Milligan, A Historical Trial of Contemporary Significance, 37 Ind. L. Rev. 661 (2004).

Thompson, Antonio Scott. Men in German Uniform: German Prisoners of War Held in the United States During World War II (2006) (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Kentucky).